The rise of domestic outsourcing and how it’s different from offshore: As we emphasized in our previous post, building and executing an optimal talent management strategy is about finding the perfect balance among full-time direct hires, contingent staff, consultants and outsourcing delivery centers.

It’s about creating flexibility in your strategy so you can flex up and down or shift among talent channels (for example, consulting to outsourcing) because of cost, risk or capability trade-offs. Companies looking to add outsourcing to the flex sides of their talent portfolios need to thoroughly evaluate both risks and rewards associated with offshore and domestic delivery center options.

Key questions for balancing between offshore and domestic outsourcing should include:

- In context of our delivery model, which skills and capabilities need to be on site, which need to be in close proximity and which are perfectly insensitive to location, time zone and so forth?

- What is the ratio of hard to soft skills required? Hard skills are easily defined and lacking in gray areas. Soft skills are less tangible and include communications (verbal, written) and cultural, political and business acumen (for example, knowing business cultural norms and mores, comprehending and acting upon needs without being asked or told explicitly, ability to read social cues, cultural work ethic, etc).

- Will work product be the same no matter where the activity is performed (i.e., is the work commoditized/fungible or might it be influenced by context)?

- What is our level of trust and rapport with the outsourcing service provider? (i.e., how transparent are they willing to be with respect to services/skills bundling, recommendations, costs and pricing)?

- How can we integrate the outsourcing service provider’s talent pipeline as our staff to flex ratios shift over time?

- What are prospective outsourcing providers’ employee turnover rates and can the information be verified independently?

- What are the outsourcing providers’ approaches to mitigating risks of talent-market saturation or rising attrition in given markets?

- And what is our own outsourcing maturity? How experienced are we at defining our requirements and understanding if the right levels of resources are being recommended? Do we have strong capabilities for measuring and managing service providers’ performance?

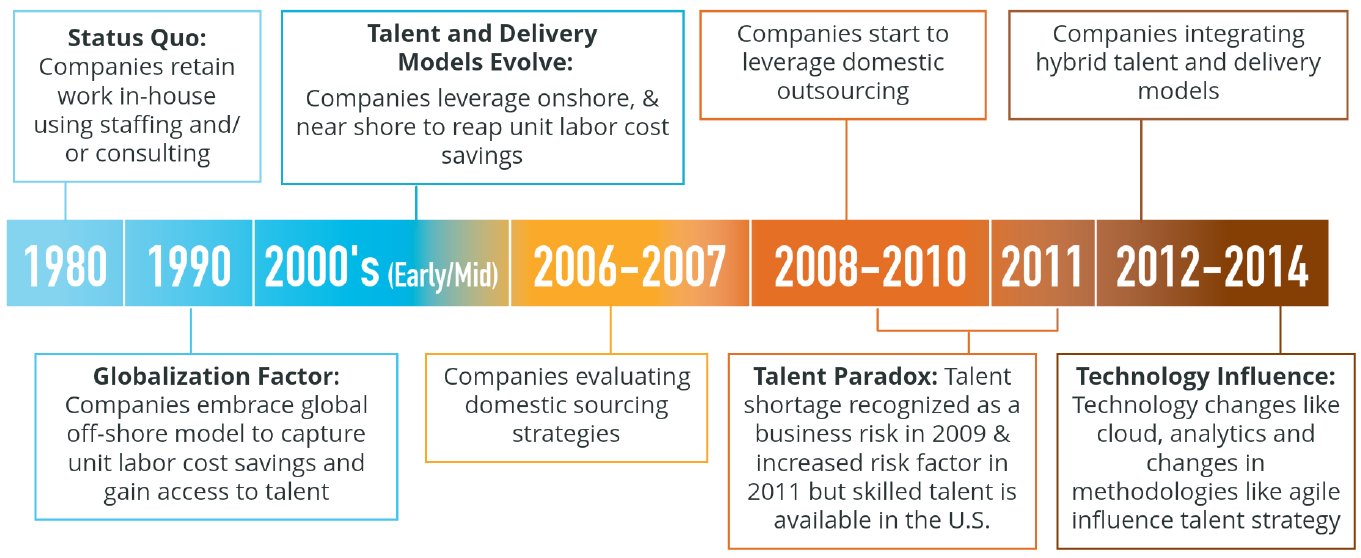

Starting over twenty years ago, companies typically pursued offshore outsourcing as a means to access low-cost talent and to align with their globalization strategies. Work was performed outside the four walls of a company and outside U.S. borders in supplier-owned delivery centers. But as the timeline below shows, the strong bias to offshore began to shift around the year 2000 and has continued to evolve to a point where outsourcing is no longer synonymous with offshore.

The shift has continued to evolve as U.S. corporations asked some tough questions:

-

Have we sent too much offshore?

-

Have we sent the right types of work and/or roles offshore?

-

And, since we first began sending work offshore, have there been changes in our end markets, our product development models, operations and service-delivery models or compliance/regulatory requirements that would dictate a reevaluation of where the balance should be between offshore and domestic options?

Due to large labor-cost differentials between developed and emerging global economies, most corporations operating in mature industrial economies assume that, given parity in skills, global offshore is always the more cost-effective solution. Beyond perceived cost differences, offshoring decisions continue to focus on accessing low-cost talent from such global markets as Brazil, China, Vietnam and others but may also be driven by mergers and acquisitions or other top-line objectives such as growth strategy, brand globalization or diversifying manufacturing.

At the same time, there is enough talk in the U.S. business community to suggest that decisions to source talent offshore, while still very much under consideration, are now being taken more carefully than in the recent past. Companies that have invested in going offshore are beginning to understand that those investments have hidden costs and diminishing returns. What is more, it can be very difficult to move away from such decisions once they have taken firm root.

A Harvard Business Review (HBR) study among Harvard Business School alumni who have made business-location decisions in the past finds that 57% of decisions were “about potentially moving existing activities outside of the U.S.” compared to just 9% considering moves into the U.S. What is interesting though, is that while the U.S. won only 16% of decisions in the former group, it won three quarters of decisions in the latter.

Talent paradox extends globally.

As discussed in Welcome to the Talent Paradox, access to top talent is a global problem. Increasing competition and talent poaching among offshore companies continues to contribute to the growth of emerging economies and an expansion of their middle classes. As a result, wage inflation and increased employee turnover almost always ensues. According to Harvard Business Review, employee turnover rate in India is averaging at 23% while in China the rate appears to be somewhere in the 10-20% range.

Additional drivers that can erode expected cost benefits of offshore outsourcing include:

- Currency exchange-rate fluctuations,

- Rework and extended project cycle times due to language, cultural, communications, technology, time-zone and other challenges,

- Unanticipated supervisory, telecommunications and travel costs, and

- Higher costs associated with a general lack of transparency, trust and collaboration between U.S. companies and their offshore outsourcing service providers.

From a risk-management perspective, companies must also consider the potential for leaks to sensitive information and intellectual property as well as the lack of international legal standards and recourse options should critical losses occur. While this risk is present anywhere in the globe, we will explore this particular issue in greater detail in future blog posts.

Outsourcing:

While domestic outsourcing generally costs more out of pocket compared to global offshore, proper total cost evaluation extended over time may provide a substantially different picture especially when additional risks and potential associated costs are considered. At the September 2013 Global Outsourcing and Strategic Partnership Summit, the Gartner Group reported study data showing that, within a cost differential of 15-20%, senior U.S. business executives would retain work inside the U.S. to balance risks even when domestic is not the least expensive option.

Domestic outsourcing firms specialize in identifying U.S. markets with large concentrations and/or surpluses of certain skill sets and talent. Surplus talent often goes hand in hand with other factors, such as depressed commercial real estate, which enables domestic delivery centers to be cost effective while still paying middle to upper-income salaries to exceptional and experienced employees.

While some delivery center recruits will be interested in finding permanent work, a larger portion is content to work in contingent roles because they are:

- In mature stages of their careers,

- Looking for greater work-life balance,

- Tired of being road warriors,

- Wishing to avoid corporate politics, and /or

- Unable/unwilling to re-locate for family or other reasons.

By organizing contingent workforces into delivery centers, domestic outsourcing providers create benefits for delivery center professionals, including opportunities to work in roles and on projects where they can excel in environments that are free from corporate internal politics and competition. While domestic delivery center models typically have career paths, professional development and progression built in, the overarching focus is on collaboration rather than competition, which benefits delivery-center clients enormously.

Another important factor to consider when balancing domestic versus global offshore is the potential for outsourcing partners to serve as talent pipelines, especially should the expected talent crisis intensify over time. Companies will never have perfect foresight into how their technology roadmaps might open new gaps (or widen existing gaps) in their capability portfolios. Well-structured outsourcing relationships will offer opportunities for client companies to convert certain percentages of outsourced resources to permanent employees. This is an extremely low-risk way for companies to meet permanent direct hiring requirements without expensive recruitment, endless rounds of resumes and interviews and by creating opportunities for both parties to test the waters in advance of any hiring decisions.

A final consideration for U.S. companies should be their own sense of stewardship for the U.S. as a nation. In much the same way a company might choose offshore as a means for promoting end-market health and long-term growth, U.S. companies may also find lasting competitive advantage if they can become known as brands that pursue determined strategies of U.S. job creation in an economy that sorely needs it.

In our next blog post, we interview some of the professionals whose careers have blossomed in delivery center environments.